Dear Bird Folks,

I recently came across an old column of yours. It was all about the different types of bird beaks. I found the diversity very interesting. This got me thinking about birds’ feet and if they are just as diverse. What can you tell me about bird feet?

– Ted, Kingston, MA

Oh, I remember that one, Ted,

That column was written back on November 2004. John, from Brewster, submitted the question. He thought I would be the perfect person to write about bird beaks because, according to John, I have a “big mouth.” What the &%!#@ is that about? In spite of that little jab, I answered his question. But John needs to know that all these years later, I’m still looking for him. Us big mouths never forget.

When it comes to our feet, humans are boring. No matter where you go, our feet basically look the same (except for the occasional oddball with six toes). What is the purpose of our toes anyhow? I guess they help with balance, but that’s about it. The rest of our toe functions are limited to wiggling, stubbing, getting blisters, having the nail portion painted and being called “piggies” for some reason. Oh, sure, occasionally a lazy person will use his/her toes to pick up an item (usually an old sock) off the floor, but that’s about as exciting as our toes get. Meanwhile, bird toes are far more interesting. Specialty toes allow birds to walk on lily pads, dive to great depths under water, cling to tree trunks, catch fish, and hold onto branches during strong storms. (Whether birds ever use their feet to pick up old socks has yet to be proven.)

Before we continue, you should stop reading this for a minute and look at the birds on your feeder. Or, if you don’t have a feeder, open one of your bird books. (If you don’t have either a feeder or a bird book, we need to talk.) While you are looking at a bird, any bird, notice the legs. See that weird bend in the leg that looks like a backwards-bending knee? Believe it or not, that’s not the bird’s knee. Birds have knees, of course, but we don’t see them. Their knees are much farther up on the leg and are hidden under the feathers. The bendy part in the middle of the leg is, in fact, the bird’s ankle. That’s right, the ankle. The skinny part below the ankle that looks like more leg is actually the foot. Freaky, eh? The part we call the “foot” is really just the toes. And it is with the toes where the real diversity begins.

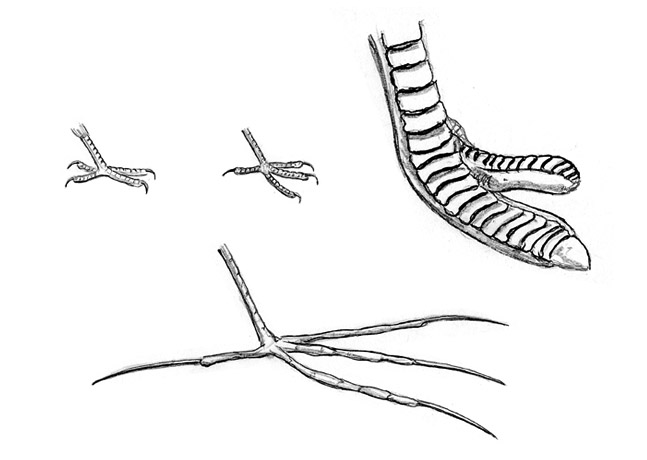

Unlike humans, who have five toes on each foot (or at least that’s the number we are supposed to have), most birds’ feet only have four toes. The typical configuration is three toes in the front and one in the back. The back toe helps songbirds cling to branches at night. When a songbird bends its ankles (the backwards-bending part that looks like it should be the knee), a tendon draws the toes together and locks the bird onto the branch. Their grip on the branch is not released until the bird stands up. This is not the setup for most woodpeckers, however. To help them maneuver up and down tree trunks, woodpeckers have two toes in the front and two facing the back. (FYI: There are a few species of woodpeckers that only have three toes on each foot, but they asked me not to point them out. They’re a little sensitive about it.) Chimney Swifts spend most of their time in the air. Thus, they have little use for their feet, except to help them cling to vertical surfaces, like the walls of chimneys. So, their toes all face forward like our toes do (but without the nail polish). Ospreys (and owls) have the best of both worlds. One of their toes has the ability to rotate from front to back, depending on the situation, or how wiggly the fish is.

The Northern Jacana, a small wading bird from the tropics, has the usual toe configuration (which is three in front and one in the back, if you weren’t paying attention earlier). But it’s the length of their toes that makes this bird different. Jacanas’ toes are super-long (nearly ten inches) and super-skinny (like E.T.’s fingers). This distributes their weight and allows the birds to walk on lily pads, much the same way we use snowshoes to walk on snow. Water birds (ducks, geese, gulls, etc.) have three of their toes connected with a flap of skin, which helps propel them on or under the water. American Coots do things a little differently. Even though they swim and dive, their toes aren’t connected, duck-style. Instead, each toe is lobed (looking as if they were flattened with a hammer), creating a foot made up of tiny individual paddles. Why do these birds have lobes instead of webbed toes? I’m not sure, but I’ll ask the next coot I see, which shouldn’t be too long. In my business, I see a lot of coots.

Grouse and other ground dwelling birds have stout toes for running and scratching in the dirt. But the bird with the strangest foot configuration is the ostrich. Ostriches are the only bird in the world with just two toes, and one of those toes is huge, almost hoof-shaped. This allows them to run over 40 MPH. In addition, only one of their toes has a nail in it. Having just one toenail is a bit freaky, but it saves the birds a lot of money on nail polish.

Your hunch is correct, Ted. Bird feet are nearly as diverse as their beaks. I appreciate the question and I also appreciate that you didn’t call me a “big mouth.” I hope John from Brewster reads this and knows I’m still looking for him. Although I probably already know who he is…as I said before, I know a lot of old coots.