Dear Bird Folks,

We used to look forward to seeing flocks of migrating Canada Geese each fall, but in recent years it seems the geese never leave our area. Or is that just my imagination?

– Mark, Plymouth, MA

Yes and no, Mark,

Yes, the Canada Geese never leave your area, and no, it’s not your imagination, but more on that later. First, I want to commend you on properly calling these birds Canada Geese. Good for you. I don’t know when the “Canadian Geese” inaccuracy began to creep into our vocabulary, but it does not appear to be stopping anytime soon, and I don’t get it. That’s simply not the bird’s name. I mean, we don’t say Californian Condor, or Rhode Islander Red or Baltimoreon Oriole, so what is with the Canadian goose thing? What are they teaching kids these days? I know things are tough for schools right now, but what’s more important than learning proper goose names? I certainly can’t think of anything.

We’ll begin our discussion of geese by talking about turkeys. Why turkeys? Remember when seeing a Wild Turkey was a rare event? Today it’s hard not to see one (but it’s still fun). Who gets the credit (or blame) for the exploding turkey population? We do, of course. First we wiped them all out and then we reintroduced them. And when the turkeys returned, they loved what we had done with the place. It turns out turkeys like suburbia as much as we do. There’s plenty of food and things are safer. The same thing can be said about Canada Geese. Our changes to the landscape have inadvertently created primo goose habitat and Canada Geese love it. (They just wish we’d learn to say their name correctly.)

Only a few centuries ago Massachusetts was heavily forested. Forests are great for songbirds and woodpeckers, but not very appealing to nesting geese. Back then geese were most often seen during migration, as they moved back and forth between their wintering grounds and their breeding grounds in Canada (or Canadian). Things began to improve for the birds when settlers cleared the land and planted crops. (Geese love open areas…and crops.) But a big boost came in the 1930s. Before that, hunters were allowed to use real birds as decoys. Tethered, live honking Canada Geese were set out to attract migrants. This brings up the question: If someone felt like eating a goose and already had a goose, why not just eat that goose instead of going through the trouble of trying to trick others with it? But whatever, the practice was eventually outlawed and the Judas geese were released into the wild (and again, still not eaten). From these released birds, a non-migrating population slowly began to develop, and develop and develop.

The next goose boost came in the form of green grass. Like many people, geese love waterfront lawns, soccer fields and golf courses, especially golf courses. Grass-covered fairways not only provided food, but they came complete with goose-friendly ponds. And because the birds were now living in a country club, things were a lot safer for them…except for having to dodge the occasional bad slice from some golf hack.

The goose population is also helped by the fact that geese are simply really good parents. By contrast, baby ducklings typically grow up in a single parent household. The hen is left alone to raise and protect her brood, while her mate goes off to molt someplace (at least that’s what he says he’s doing). Not so with Canada Geese. The male stands on constant guard. Even after the chicks have hatched, he stays and provides protection. (Any of us who have tried to take photos of those adorable goslings have learned the hard way how protective he can be.) It should also be pointed out that the adults aren’t only a couple during the breeding season. Geese pairs typically remain together forever, unless one of them is lost to a predator, hunter or a golf hack with a bad slice.

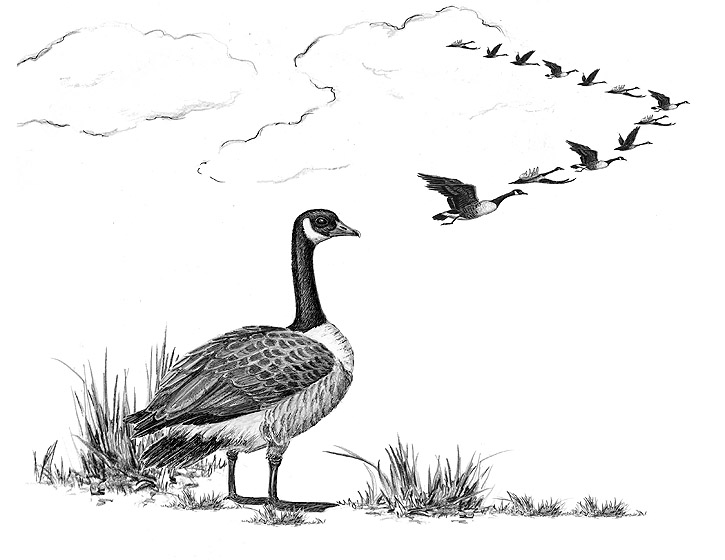

For many people, the honking of migrating geese is the sound of autumn, giving folks a warm feeling even on a cold night. This brings up the question: Why do geese honk so much? Most birds, even songbirds, give call notes in flight; their calls are comparatively softer, however, so we can’t hear them as easily. Flight calls are the birds’ way of communicating with each other and since geese are big birds, they have bigger voices. Speaking of calls: Male and female Canada Geese look basically identical, but their voices are different. The male’s voice is deeper and he gives a true honk, while the female’s call is higher pitched and sounds more like “hink.” That’s right, she has less honk and more hink. (There’s a sentence I’ll bet no one has ever written before.)

With a population of five to seven million individuals, Canada Geese are doing quite well, Mark. And much like Wild Turkeys, some folks aren’t thrilled about seeing so many geese. But much of the blame for the increase can be pointed at us and the changes we have made to the landscape, and our love of goose-attracting grass. Here’s a final bit of goose info: A flock of geese is a gaggle, unless it’s in flight and then it’s called a skein. (Don’t ask me why, or why skein is spelled like that.) Also, a baby goose is a gosling, the male is a gander or honker, and the female is simply called a goose. That seems a little dull and repetitive to me, but at least she’s not called a hinker. Imagine telling a stranger you just saw a Canadian hinker? I know I wouldn’t do it.