A surprise Northern Wheatear:

Ever heard of a wheatear? If you haven’t, here’s a hint – it’s a bird. Does that help? Earlier in the month I wrote a column about spotting an American White Pelican flying over Orleans. This is a rare sighting for Cape Cod, but the bird is so massive even I couldn’t miss it. In the same column I also mentioned that less obvious species pass through our area all the time and many go unnoticed. This could have been the case yesterday when a rare and rather ordinary-looking bird made a brief stop in Yarmouth Port. Luckily, it landed in the yard of one of the region’s best birders…and it totally didn’t go unnoticed.

I was just heading off to work when I received a text message from Alex Burdo. Alex is a former employee, a recent graduate of Brown University and a ridiculously good birder. The note said he had just seen a Northern Wheatear in his yard and suggested that I come over to see it for myself. Well, so much for getting to work on time.

Common bird names, as we all know, are often misleading. For example, the Northern Mockingbird is the state bird of both Florida and Texas, yet those two states are hardly in the North. But the Northern Wheatear is true to its name. The bird breeds in several locations around the world, including areas of Canada that are well above the Arctic Circle. From a distance, a wheatear basically looks and acts like a rather dull bluebird. In fact, “dull” might be the best word to describe a wheatear, except for one thing – its annual migration, which is unlike any other songbird in the world. Really.

Each spring, many bird species journey north to breed and raise a family. In the fall, they all fly back to the tropics or the southern part of the U.S. In most cases, the migration route is pretty much a straight shot, unless the birds are wheatears. Then it’s crazy. Instead of flying south with everyone else, wheatears fly east, across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe and then on to Sub-Saharan Africa, where they spend the winter. That’s right, these little bluebird-sized birds leave Canada in the fall and make a 4,500-mile perilous journey to “nearby” Africa. Wow! (I know some people don’t like going to Florida for the winter, but wheatears must really hate it.)

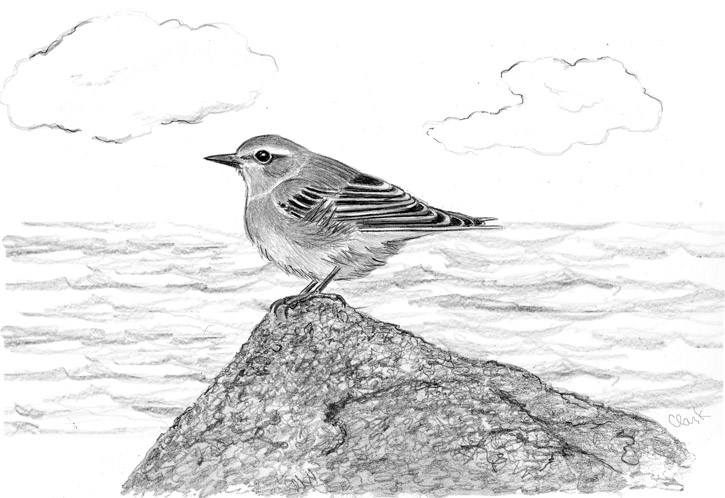

I had never been to Alex’s house before, but as soon as I arrived I knew I had found the right address. There was a mockingbird sitting on his roof and a Red-tailed Hawk on his chimney. This house belonged to a birder all right. Alex came out to greet me and immediately began showing me where he had last seen the wheatear. I very much wanted to see this rare bird, but I was having a little trouble staying focused. His house overlooks a saltwater marsh and there were birds everywhere. Egrets and herons were feeding in the tide pools, while dozens of swallows flew just above the grass. And the big hawk was still on the chimney. Alex finally got tired of my inattentiveness, and snapped, “The wheatear is right over there.” I turned, and sitting on a rock in front of his neighbor’s house was a small, nondescript bird. Most people wouldn’t have given this bird a second look, but Alex knew what it was right away and sent out an alert. For birders, seeing a Northern Wheatear in Yarmouth Port is a big deal. It’s nearly as big as seeing Bruno Mars sing at a wedding in Chatham. Although in this case, there was no security and no one had to dress up. (Birders will do pretty much anything to see a rare bird, except get dressed up.)

Alex gave me a brief natural history lesson on the wheatear and how it was once thought to be in the thrush family (like bluebirds), but are now considered to be Old World flycatchers. I only remember about half of what he said, as I kept looking back at the hawk. (It was huge.) I eventually thanked him for inviting me and headed over to a nearby town landing, where there was a small crowd of people and they were all clutching binoculars and cameras. The news of the wheatear, like that of Bruno Mars, had gotten out and folks from all over came to see it. They weren’t disappointed. Every time the little bird hopped from one rock to the next, the cameras clicked away. Two passing women asked me the reason for all the excitement and when I told them about the wheatear, they seemed disappointed. I think they were hoping to see a Snowy Owl or at least a bird with a name they recognized. Speaking of the name…

The name “wheatear” has nothing to do with the birds eating wheat, which they don’t because they are flycatchers (in case you forgot already). And while they do have ears, no one can see them hidden under their feathers. Wheatear is actually a corruption of the words “white arse” (sorry, kids), referring to the birds’ bold white rump patch. I was going to explain all this to the two questioning women, but they had heard enough bird talk for one day and had moved on. I didn’t blame them.

Seasonal bird migration is a predictable phenomenon, but it’s not always perfect. Occasionally, a bird will end up where it shouldn’t be. In this case, that wheatear was headed to Sub-Saharan Africa, but somehow it landed in Yarmouth Port, which is understandable. A lot people get those two places mixed up. Sometimes a rare bird is so small and plain that only a top birder like Alex can identify it. But when a bird is large, with obvious markings, and still needs to be identified, that’s where I come in. After all, I figured out a pelican all by myself. Let’s not forget about that.