Dear Bird Folks,

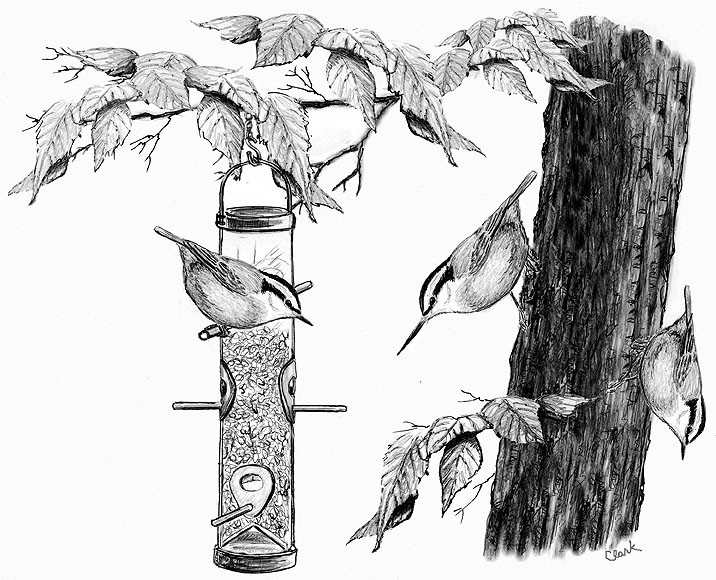

Please take a look at the attached photo of this Red-breasted Nuthatch. It seems to have an extra long, hummingbird-style beak. We call it a “hum-hatch.” Any explanation?

– Rocky, Eastham, MA

This could be big, Rocky,

One of the major drawbacks of being in the bird feeding business is that there’s rarely anything new. Other industries are continuously designing refreshed cars, TVs, video games, etc., but birdfeeders have been basically the same for decades. And it’s been eons since a different bird species was invented. The idea of a totally new bird, one that’s half-nuthatch and half-hummingbird, would be both cool and a boon to business. Unfortunately, this is not the case here. There is something wrong with the bird in your yard, which means I have to give you a serious answer and I hate doing that. Oh, well. Here goes.

It’s hard to overestimate how important beaks are for birds. They use them for protection, to build their nests, gather food and make themselves look pretty. From pelicans to parrots to hawks, the beaks of birds are diverse and varied, and critical to their survival. An imperfect beak makes life more challenging than it already is. This brings us to the bird in your yard. Why would the beak of a Red-breasted Nuthatch grow twice as long as normal? Did it actually mate with a hummingbird? Could it be a birth defect or caused by an injury? Or did the beak grow longer because the bird simply told too many lies, a predicament known as “Pinocchio Syndrome”? Look it up if you don’t believe me. Speaking of looking things up…

When I first saw your bird, I thought it was a victim of messed up genes. Then I did some digging and discovered that this problem is bigger than just one odd nuthatch. In distant Alaska, folks have been reporting a number of chickadees with overgrown beaks. In several cases the beaks have grown so long they’ve crisscrossed, like a pair of scissors. Officials soon began calling this strange malady “Avian Keratin Disorder.” (Don’t ask me why they didn’t go with Pinocchio Syndrome. That’s a much better name.) Keratin is the stuff our fingernails are made of and it’s also the substance that makes bird beaks tough. It allows woodpeckers to dig into trees, oytercatchers to bust into shellfish and nuthatches to hatch open seeds. For some reason, keratin is getting out of hand in Alaska. What’s the cause: truama, diet, pollution, chewing tobacco? Nobody knew, but it was time to find out.

Researchers immediately began looking into pesticides and pollutants, which made sense since bad substances are found everywhere, even in Alaska. But tests on the affected birds found pollutants weren’t the problem. Diet was another possibility, especially since many of the deformed birds were eating from bird feeders. Wait, what? Bird feeders? Uh-oh! Officials quickly decided that bird feeders weren’t the issue either. (Phew!) The troubled birds were only attracted to feeders because foraging in the wild was becoming too difficult. One by one, possible causes were eliminated. Then a team from the University of California San Francisco and the U.S. Geological Survey discovered a new virus (oh no, not another virus), which was found in 100% of the birds with freaky beaks. The virus, soon to be called “poecivirus” (from the Latin for Black-capped Chickadee), is not confined to either Alaska or chickadees. It has also been discovered in other North American species, including nuthatches. Birds with odd beaks in other parts of the world are also going to be tested. There’s concern that Avian Keratin Disorder may be a global problem. Swell.

Can birds survive with these deformed beaks? Not very well, but at least a few of them have adapted, although there’s likely a lot more that haven’t. It’s important to remember that birds not only use their beaks for eating, but for many other important functions, including preening. If birds can’t keep their feathers properly maintained, no amount of eating is going to protect them from the winter elements. What is being done to help the birds? Right now not much, except to try to understand the scope of the disorder. Poecivirus is the common link, but officials aren’t totally sure if it’s even the cause. There are still too many unanswered questions, including how the virus is spread. The kneejerk reaction is to point a finger at bird feeders; after all, this is where birds tend to gather. But some species with the problem aren’t feeder birds, so there must be something else going on. In their quest to find the answers, researchers are looking for our help. They are asking citizens to report any birds they see with strange beaks. If you search “Beak Deformity Observation Report,” you’ll find an online form to fill out. Don’t worry, it’s legit. You won’t end up with a weird magazine subscription or an extended warranty for your twenty-year-old car.

Without performing a proper test, Rocky, you won’t know for sure if your “hum-hatch” is just an odd bird (a small percentage of birds are normally born with deformed beaks) or if it actually has the poecivirus. But either way, it’s safe to assume that this is an avian dilemma only and not a problem for humans. In other words, if you wake up one morning and discover that your nose has grown longer, rest assured that you don’t have Avian Keratin Disorder. It’s probably just a touch of Pinocchio Syndrome. That happens to me a lot.