Dear Bird Folks,

I live near the big rotary in Orleans. At least once a day a noisy flock of Canada Geese flies just above my house. Often, a larger flock of ducks will also fly over, but the ducks are too high to be identified. Any idea what kind of ducks they are?

– Sarah, Orleans, MA

They’re eiders, Sarah,

The ducks you are seeing are Common Eiders. They could also be scoters, which are ducks, too, but since I haven’t written about eiders for a while, I’m going with them. Besides, I’m never wrong. (Just don’t read the column I wrote two weeks ago about storks. That was a bad day.) Weighing twice as much as a Mallard, the Common Eider is the largest duck in North America. As the name implies, Common Eiders are indeed common, or at least they are in our area. I remember reading about them in my first bird book, the Golden Guide to the Birds of North America. The book stated that eiders are rare in most locations, but spend the winter in huge rafts off the coast of “Chatham, Mass.” I thought that was so cool. I couldn’t think of another instance where a field guide actually mentioned a specific town. Then someone pointed out the “Baltimore Oriole.” Oh, right. I forgot about that. Still, seeing a Cape town mentioned in a field guide was pretty cool.

Rarely found away from the coast, eiders are true sea ducks. The majority of these hardy birds breed in Greenland, along the coast of Alaska and in parts of Canada that are so far north even Canadians doesn’t know about them. Smaller populations also breed along the rocky coast of Maine and a few even nest here in Massachusetts. But winter is when we see eiders in serious numbers. Forced south by ice, eiders by the hundreds of thousands descend on Cape Cod each fall to ride out the winter in our comparatively warmer waters. Here they feed on mussels and other mollusks, which upsets some locals. (But what doesn’t upset some locals?)

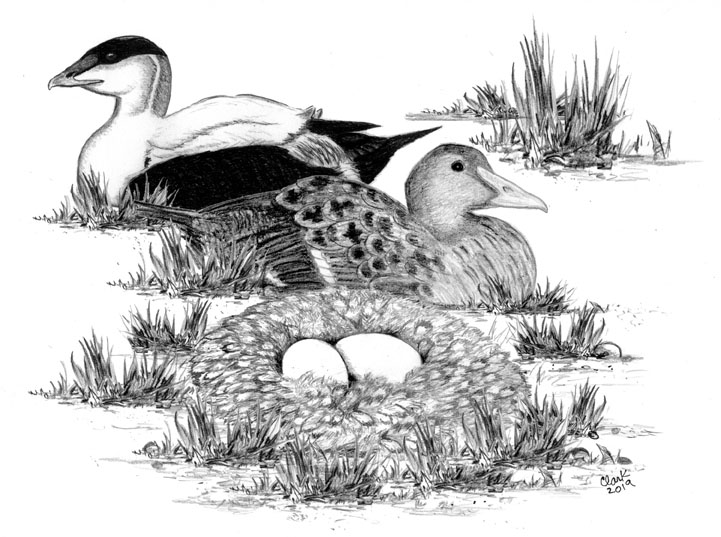

Because they are sea ducks, eiders tend to avoid flying over land. The Cape, however, is fairly narrow, especially near the Orleans rotary. Ducks flying high over the bay can see the ocean on the other side and will routinely zip across the thin strip of land. But unlike geese, which customarily fly fairly low and in orderly V-shaped flocks, an eider flock tends to be higher and far less organized. (A bird with OCD would never make it as an eider.) Female adult Common Eiders are a warm rusty brown, while the more distinctive males are stately black and white. Identifying adult eiders is fairly easy, but sorting out the young birds can be tricky. For the first few years of their lives, young males are a mixture of black, brown, white and blotchy. They look like a totally different species, except for one thing…the beak. Eiders, both young and old, have a long, doorstop-shaped beak. It’s a feature they can’t get away from, and that’s okay with them.

An eider’s beak may be a bit chunky, but it’s perfect for gathering its favorite food, blue mussels. Have you ever tried to pry a mussel off a rock? It’s not easy. Now try doing it with your mouth, while swimming under water. The eider’s large, powerful beak has little trouble extricating even the most stubborn mussel. Speaking of powerful: Once a mussel is dislodged, it is swallowed whole, shell and all. There is no chewing, steaming or adding butter. The mussel then encounters a different muscle, the bird’s gizzard, and tough shellfish are no match for an eider’s gizzard. Here’s an odd factoid: Because of its diet, an eider’s droppings contain a high percentage of sharp shell fragments. Ouch! (And I thought I had problems after eating corn on the cob…if you know what I mean.)

Most people, even non-birders, are familiar with eiders because of their feathers. Eiderdown has long been used as a source of insulation. Breeding females line their nest with their own soft, downy feathers. In most cases, these nests are in fairly remote locations, but in Iceland the birds set up colonies right near people. This allows local “down farmers” to collect the soft feathers. Some collecting happens at the end of the breeding season, while other farmers gather down at various times during the summer. If the female discovers that her nest has been robbed of feathers, she will quickly replace them with more of her own. I know stealing the hen’s feathers sounds like a mean thing to do, but at the same time the farmer is giving her a totally safe place to live. Eiders in other parts of the world are constantly dealing with dangerous predators, but not in Iceland. In Iceland, the female, her eggs, her chicks and especially her feathers, are well guarded.

This brings up a timely and sensitive topic. During the holidays, people like to give each other down jackets, pillows, etc. This is not a good idea. A comforter made from humanely collected eiderdown typically sells for $10,000. Cheaper products are likely filled with feathers produced in China, taken from birds that are continuously abused. Since it’s the festive season, I won’t get into the ugly details. But if you look it up, you’ll see. Enough said.

Most of our eiders are out at sea, Sarah, but if you want to get a closer look at one, swing by any Cape Cod harbor. There always seems to be a few birds taking a break from the turbulent ocean. But unlike geese, eiders tend to be silent, producing only the occasional groan. I don’t know what the groaning is all about, but it probably happens when the bird passes some of those shell fragments…if you know what I mean.