Dear Bird Folks,

This might seem like an inappropriate question for the summer, but I’m wondering where the juncos have gone. Our yard was full of them in the winter, but now they seem to have disappeared. Are they totally gone from our area, or have they just left my yard?

– Aimee, Sandwich, MA

Not a problem, Aimee,

I don’t think your question is “inappropriate,” and believe me I get a lot of inappropriate questions. The other day a guy walked in and asked if we carried “cat toys.” Cat toys!!! Now that’s inappropriate. It’s like going into a gift shop at the Vatican and asking for a framed picture of Satan. (That last line was just to illustrate a point. I wasn’t equating cats to Satan. I would never do that to him.)

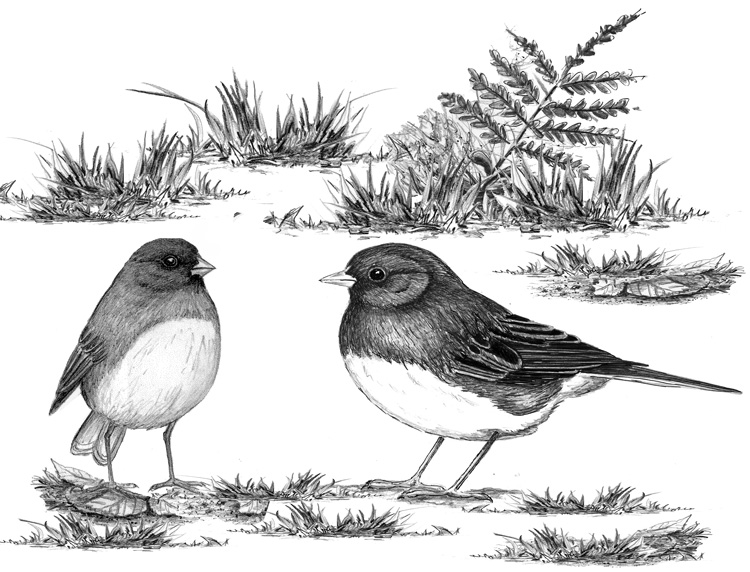

Believe it or not, there’s an organization that keeps track of which birds regularly come to our birdfeeders. No, it’s not the NSA, or even the Russians; it’s Cornell University’s Project FeederWatch. For nearly thirty years Cornell has asked citizen scientists to keep a journal of the birds that visit their feeders. Wanna guess which species is seen the most? Chickadees? Cardinals? Jays? Those darn blackbirds? The answer is none of the above. According to Project FeederWatch, Dark-eyed Juncos are seen at more feeders than any other species. (So much for those darn blackbirds “taking over” all the birdfeeders.)

The interesting thing about juncos is, they don’t even like our yards. They only visit when they can’t find a better alternative. That’s right, we are the junco’s version of Denny’s. It’s not that juncos hate our birdseed, but they would much rather eat natural food, in a natural setting. But when snow covers the landscape the birds switch to plan B, which is us. Because juncos tend to visit us more in the winter, many folks refer to them as “snowbirds.” And just like robins are thought to be the first sign of spring, the arrival of juncos means it’s time for you to put away the lawn furniture and put up the storm windows…or in my case, get my wife to do it.

Why are they called “juncos” instead of “snowbirds”? Who the heck knows? John James Audubon, as well as other early naturalists, called them snowbirds. But somewhere along the way their common name became junco, perhaps from their Latin name, Junco hyemalis. And to make things even more confusing, juncos are actually sparrows. Yup, they could have been called “gray sparrows,” but that would have been too easy.

More often than not, if you see one junco, you’ll see several. In the winter, juncos tend to move about in small flocks. They are social birds and enjoy each other’s company, but that doesn’t mean they get along. As with many birds, there is an actual pecking order. Typically, an adult male will assert his dominance over other flock members. Younger males are next in line, followed by adult females. But unlike some human societies, where those at the top always stay at the top and the bottom folks aren’t allowed to move up, juncos are not so subservient. The bottom birds are always challenging the upper birds, causing much in-flock fighting. Come spring, the flocks break up, the fighting ends, and the birds settle on the breeding grounds…where they fight over that. Most juncos spend their summers in the conifer forests of the northern U.S. and in Canada. On the breeding grounds they feed on a variety of natural seeds, including pigweed. I don’t know what pigweed is but next to stinkweed, it has one of the best plant names ever. Juncos also consume large amounts of insect matter, including spiders and spruce budworms. They may also eat stink bugs, or maybe not. I just wanted to write “stink” one more time while I had the chance.

The juncos you see in the winter, Aimee, haven’t totally abandoned you. They have temporarily moved to their breeding grounds. Some juncos breed right here in Massachusetts (usually in the Berkshires), but the bulk of them, an estimated 600 million, breed up in Canada. Not to worry, though. Once summer is over and winter returns, the snowbirds will once again be back at your feeder. So, stock up on pigweed while you can.

Speaking of Canada:

For a reason only known to Canadians, Canada didn’t have a national bird. So, in 2015 the National Bird Project invited Canadians to vote for their national bird. Upon hearing the request, a seventh grader in Toronto asked me to write a column in support of the Black-capped Chickadee, which, of course, I did. Well, I’m sorry to say that after all the votes were counted, the chickadee didn’t win. (So much for my clout.) The top vote getter was the Common Loon, followed by the Snowy Owl. But apparently officials didn’t like the people’s choice and have since declared the Gray Jay as Canada’s national bird. While I like Gray Jays and admit it’s a pretty cool national bird, I can’t help but feel that this is yet one more example of the popular vote being ignored. I think we all know of another recent popular vote that was also disregarded. That’s right, I’m talking about the naming of Boaty McBoatface. I’m still upset over that one.