Dear Bird Folks,

Could you please tell me what bird is in the attached photo? It was feeding in a muddy pond not far from my house. It looks like a shorebird, but it’s a long way from the “shore.”

– Dave, Franklin, MA

You are right, Dave,

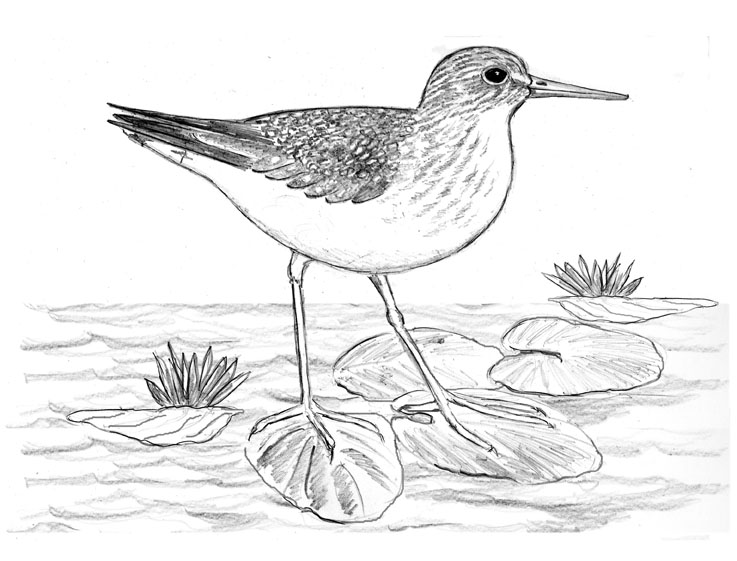

The bird in your photo looks like a shorebird, because it is a shorebird. It’s just not a saltwater shorebird; it’s more of a muddy pond shorebird. Did you follow that? When most folks think of shorebirds they think of the sandpipers we see feeding on mudflats or on the beach, probing in the sand just out of reach of the waves. But there are a few sandpipers that aren’t into the beach scene and the bird in your photo is one of those. It’s a Solitary Sandpiper and it prefers muddy ponds to salt marshes and lily pads to seaweed. If you don’t know much about this bird, don’t feel bad. Nobody else knows much about it either. Really.

One legendary non-shore shorebird is the American Woodcock. While classified as a shorebird, this odd creature would look out of place on the beach or in just about any other location. But this is not the case with the Solitary Sandpiper. It has all of the classic sandpiper features including: long legs for standing in shallow water, an extended beak for digging into muck and the generic shorebird plumage. It’s the bird’s habitat of choice (bogs and ponds) that makes it different. You know those old personals ads that said: “Likes to take long walks on the beach” or “Enjoys watching the sunset over Cape Cod Bay”? You will never see one of those ads written by a Solitary Sandpiper. They have no use for any of those things…or each other.

While the sandpiper part of this bird’s common name is a bit misleading (it’s more of a “mudpiper”), the “solitary” component is perfect. Not only do Solitary Sandpipers hate the beach, they don’t care much for other sandpipers either. Hanging out with a flock of buddies is not for them. More often than not, we see them dining alone. They also eat in some rather sketchy locations. For example, one corner of the parking lot behind my shop is often underwater. Why? Old timers say that before the bulldozers moved in, my property was a productive cranberry bog. (Don’t tell the EPA.) A few years back, after a long period of rain (remember rain?), this wet area began to look pretty gross. Well, it seemed gross to us, but not to a passing Solitary Sandpiper. For three straight days the lone bird happily picked through the murky puddle, likely looking for earthworms (or maybe old birdseed or really, really old cranberries). The bird actually seemed to enjoy being there, as it wasn’t bothered at all by the noisy cars, trucks, and the stream of customers complaining about squirrels.

In addition to being loners and not liking the beach, Solitary Sandpipers do something else that separates them from their relatives: they nest in trees. When a baby songbird hatches out of its egg, it is naked, blind and entirely dependent on its parents for survival. Young sandpipers, on the other hand, are precocial, meaning they are born feathered, able to see and ready to feed themselves. Precocial birds typically nest on the ground, because that’s where their food is. All the little birds have to do is step out of the nest and start poking in the grass for their first meal. But there’s one drawback: a ground nest is easy pickins for any passing predator. Solitary Sandpipers have addressed this predicament by laying their eggs in the relative safety of tall trees. But there’s a problem here, too: These birds have zero carpentry skills. They can’t build a simple nest or anything else, even with Legos. What do they do? They become squatters, like a visiting friend from college who won’t take a hint.

Instead of going through all of the trouble of gathering sticks, grass and other material, Solitary Sandpipers just look for a nest that has already been constructed and move in. What a great idea. I don’t know why more birds haven’t thought of that. The next question is: Do the original property owners fight the sandpipers for the nest? That’s an answer we don’t know, or at least I don’t. The majority of the commandeered nests appear to be older nests previously used by songbirds, such as jays, robins, waxwings and blackbirds. Whether the sandpipers also move into active nests isn’t totally clear. It’s also not clear what happens to the baby sandpipers once they hatch and how they obtain their first meals. Remember, these are precocial babies and thus aren’t fed by their parents. But they can’t fly either. How they transport themselves from a nest that’s way up in a tree to the ground way down below remains a mystery. The most likely answer is that they simply freefall, Wood Duck-style, but actual proof has been tough to find…and the baby sandpipers refuse to talk about it.

With a few exceptions, Dave, most of North America’s Solitary Sandpipers breed in Canada and spend the winter in Central and South America, which means we only see them during spring and fall migrations. And because of their remote breeding locations, and their solitary-ness, there’s a lot we don’t know about these non-shore shorebirds. All we know is that they nest in trees, and don’t care much for long walks on the beach or sunsets over Cape Cod Bay. But they do like a nice quiet mud puddle once in a while, which is sometimes all anybody needs.