Dear Bird Folks,

Each spring I look forward to the return of the phoebes that often nest under the overhang of our shed. But it’s now November and the phoebes are still around. Shouldn’t they have migrated south by now?

– Katelyn, Provincetown, MA

It’s a strange year, Katelyn,

I’m seeing phoebes, too. Why are they still here, you ask? It’s probably because no one else left the Cape at the end of the summer, so the phoebes must have figured they shouldn’t bother leaving either. It’s just another odd thing to add to the wild year that is 2020. When the future history books are written (future history?), there’ll be much discussion about this year’s awful fires, intense politics, global pandemic and Cape Cod’s lingering phoebes. I don’t know which of those entities will have the greatest lasting impact, but I’ll be discussing phoebes today. We can all use a break from that other stuff.

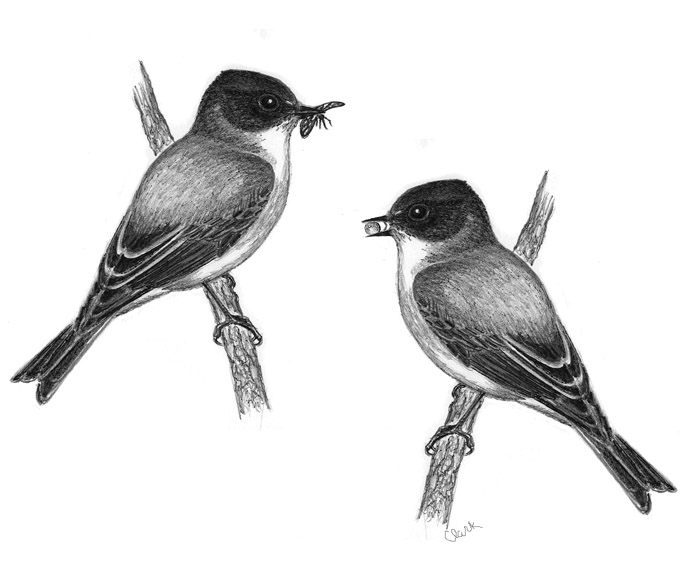

Many birds are readily recognized by their bright, distinctive plumages, but the same thing can’t be said for Eastern Phoebes. They are dullards in the plumage department, resembling washed-out juncos, which aren’t too flashy either. But looks aside, phoebes are birds that many people think of fondly. Often returning when winter is still in the forecast and we are still dressed in layers. But one day in mid-March, I’ll step outside and hear the nearly forgotten sound of, “fee-bee” break the cold morning air, and it will put a smile on my face for the rest of the day. Like bobwhites, Whip-poor-wills and chickadees, it is the phoebes’ distinctive song that gives this species its name. When you hear that raspy “fee-bee” coming from a nearby branch, you know exactly which bird is saying it. Naming the bird after its song makes sense, but what doesn’t make sense is the spelling. How did fee-bee turn into phoebe? My theory is that some bird nerd spelled it that way just as a joke and it somehow stuck. Thanks a lot, bird nerd.

In addition to being harbingers of spring, phoebes also eat lots of insects. They are, after all, flycatchers, spending most of their waking hours sitting and waiting for passing flies, wasps and moths. And while many birds tend to avoid people, phoebes actually like us, or at least they like our structures. Phoebes regularly build their mud nests under bridges, under porches or, as in your case, under the overhangs of sheds. One particular nest, which many birders are familiar with, is under the roof of the restrooms at the Beech Forest in Provincetown. Beech Forest is a noted hotspot for migrating spring warblers. On any given May morning, before heading down the trail, many birders will stop at this restroom to see the phoebes (and perhaps for another reason, since Provincetown can be a long drive). It’s always a bit awkward when other people see me staring at the bathrooms with my binoculars, but I do it anyway. The birders understand…I hope.

We humans might have a fondness for phoebes, but phoebes don’t much care for each other. They tend to be solitary birds, feeding, roosting and migrating alone. Even during the breeding season, the female barely tolerates her mate. She alone builds the nest, incubates the eggs and broods the chicks. If the male happens to stop by to see how things are going, he’ll often be chased away. Mrs. Phoebe can be a bit moody, but she’s also practical. In order to save time and energy, she’ll routinely reuse a nest from a previous year. She’ll even take over nests that formerly belonged to other birds, especially Barn Swallows. When the returning swallows discover that their old nest is now occupied, they’ll complain about it. But the early-arriving phoebes merely cite the “you snooze, you lose” rule, which apparently is valid even in the animal kingdom.

All summer long phoebes gorge themselves on an assortment of insects, but come fall our insect population begins to dwindle. But phoebes like it here and often want to extend their stay for as long as they can. What do they eat when the bugs are gone? I asked a birder friend that exact question and he replied that phoebes are “berry eaters.” To me a berry eater is a person who even tree huggers make fun of, but it simply means phoebes have the ability to incorporate vegetable matter into their diet. Using this secondary food source allows phoebes to remain here long after the insect supply has petered out. In other words, eat your veggies (and berries). In addition to arriving early and staying late, and repeatedly saying their own name (regardless of how the nerds spell it), phoebes have another distinguish phoebes from the other equally bland flycatchers. But the birds don’t do all this pumping just to help us with identification. It is thought the action warns potential predators that the little bird is aware, focused and agitated. In other words, don’t mess with this berry eater.

Eventually though, Katelyn, the cold weather will force the phoebes to head south and we’ll have to fend off winter by ourselves. But then one day in March, when things seem the gloomiest, you’ll step outside and hear a raspy, “fee-bee.” That will be an indication that winter is winding down, the year 2020 is long behind us and it’s time to look forward to future history.